April 12, 2018

Science fair veterans offer five tips for a successful project

The Calgary Youth Science Fair — taking place this weekend on the University of Calgary campus — is the largest regional fair in Canada with close to 1,000 student participants competing at the annual event. Here, three science fair experts share their best advice for not only impressing the judges but also getting the most out of the science fair experience:

Chuck Buckley is the director and president of the non-profit Calgary Youth Science Fair, which is in its 56th year. He has been volunteering with the organization since the 1980s. This is his second term as president and he judges regularly.

Mehul Gupta is a first-year UCalgary student pursuing a Bachelor of Health Science at the Cumming School of Medicine. In 2017, as a Grade 12 student, he won the Calgary Youth Science Fair’s top prize, the University of Calgary’s Chancellor’s Bursary, valued at $2,500, for his project on a type of brain cancer. His full project name was Minimally Invasive Diagnosis of AT/RT (atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumour). This year he is one of 600 volunteer judges at the science fair.

Sarah Hyslop is a fifth-year geology student in the Department of Geoscience in the Faculty of Science and is set to graduate this spring. She participated in the Calgary Youth Science Fair for eight years. Her microbiology-focused projects on everything from bats to plant oils to horseshoe crabs were gold-medal finishers four years in a row — and took her to the national Canada-Wide Science Fair from 2009 to 2012. She also competed at the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in 2013. This year she is volunteering to help hand out science fair medals.

1. Pick a project you love

“The key to a good science fair project is all about having a good question and following up on it well. If the topic is near and dear to your heart you will do a better job because you have a personal interest in the area you are pursuing,” says Buckley. “One exhibitor who really liked snakes had been volunteering, with his Dad, with a conservation group studying garter snakes in Fish Creek Park. All that time he spent volunteering with the snakes led him to ask more questions about them. He was able to use the conservation group’s data for his science fair project.”

2. Don’t be afraid of failure or admitting you don’t know the answer

“If you get a question from the judges and you don’t know the answer, admit that you don’t know. But use what you do know to try to come up with some sort of answer. Show that you can apply the knowledge that you do have to work toward an answer,” says Hyslop.

“You don’t have to have a successful experiment to win. We have a student who is trying for the third or fourth time to train snails. The snails wouldn’t train. But the project was focused on the scientific method. It has been one of the top 12 at CYSF and it has gone on to compete at the Canada-Wide Science Fair. The judging process and scoresheet favours the scientific method and awards points for scientific methodology. Even if the experiment goes completely wrong, you can still get a high score,” says Buckley.

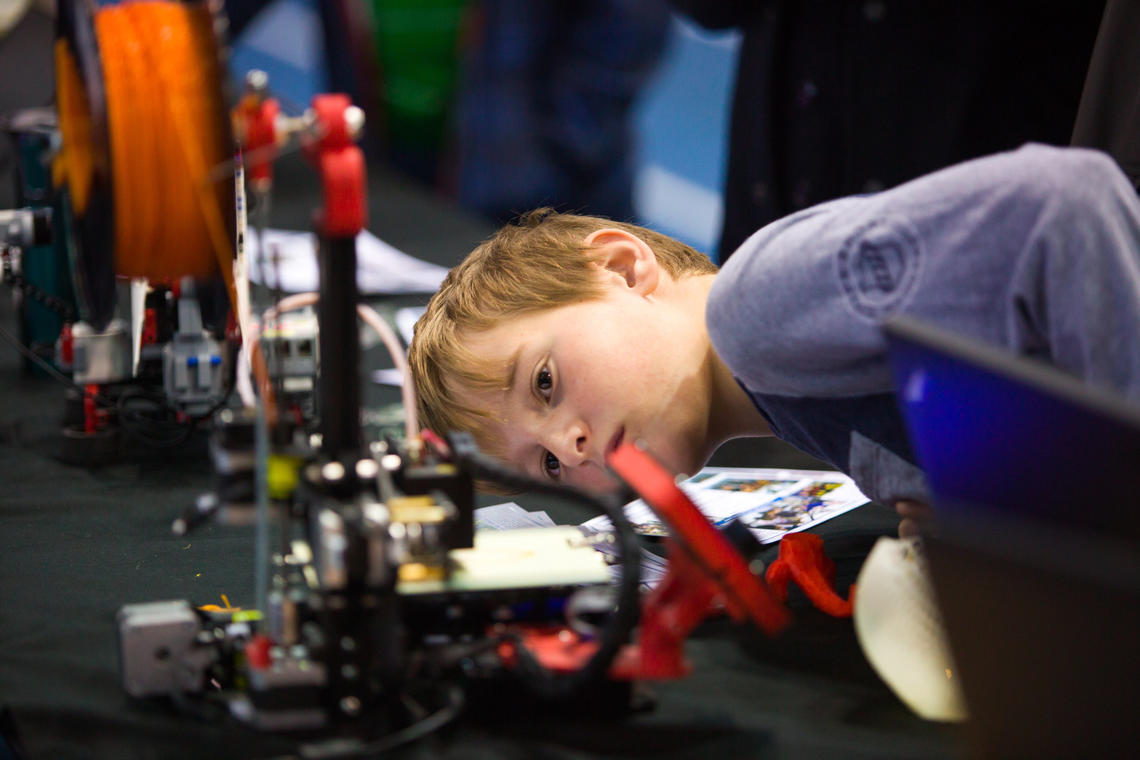

Students can enhance their science fair experience by taking in interactive booths.

Riley Brandt, University of Calgary

3. When presenting, come out of your shell and be confident

“Confidence is key when you are presenting anything,” says Gupta. “Be confident in what you know and what your project is. Don’t fall into that mindset of ‘My project’s not the best’ or ‘I didn’t have time to finish this particular part of it’ or ‘I’m not the best speaker or writer.’ Just be confident in what you do have and that will really show to the judges. And having visual aids is really important. Everyone in science fair has a poster, but any tactile little thing that you bring in that is a model or a sheet of paper with a summarized version of your poster, anything like that helps judges to remember and learn about your project and understand it more clearly.”

“Typically, in the first round of judging, each exhibitor will present to three or four judges for about 15 minutes and then answer questions for about 5 to 10 minutes,” says Buckley. “As the judging goes on, many participants get better as they go — they overcome their nerves and start to relax. So remember that you get multiple chances to make a first impression and practise face-to-face interaction. That human-to-human interaction is a very important skill to develop.”

4. Have fun and make friends

“Many of the exhibitors are so nervous about their own projects on the first day that they forget to look at the world around them. One of the best ways to have a great science fair experience is to mingle with other participants and get to know each other and have fun,” says Buckley.

“The best part of science fair was the friends I made,” says Hyslop. “There was this pack of us that kept going every year. We would cheer each other on and hope that we would all make it to the Canada-Wide Science Fair or other international fairs so we could travel together. Even though I don’t see all of them now, we all try to get together during the summer or Christmas break and have a hang out.”

“One of the most important things is the community that you build,” says Gupta. “A lot of my friends, and some of my best friends, I made through science fair. Sunand Kannappan won science fair the year before me and we are very good friends. We are in the same year and in the same program now at the University of Calgary. We have started different clubs and we both volunteer with the science fair now. It has been great to know him through science fair and then transition that relationship to university.

"So a piece of advice I would give to people on the day of the fair is to talk to a lot of other people about their projects. Learn more about the regions of science that you don’t often see in your classroom. I learned about entirely new fields of science by doing that — and I made friends in the process.”

5. Look for ideas everywhere and seek out mentors

“Even as a high school student, don’t be afraid to reach out to labs where you are interested in their work, just Google them and call them up,” says Gupta. He came up with his gold-medal winning 2017 CYSF project idea a few years ago after visiting Jaipur, India, where his grandmother lives, and volunteering at a school there where children were suffering from brain cancers, cerebral palsy and neurological disorders.

“When I came back I wanted to do research to study the effects of that,” he says. So Gupta went to the Alberta Children’s Hospital website and read all the bios in the database of researchers. “I shortlisted a couple and I just emailed them and said that I was a Grade 11 student and that I’d love to be in your lab and get to know what scientific research is like.”

Gupta heard back from Dr. Gerald Pfeffer’s lab — and the rest is history. It may seem far-fetched, but Gupta says that this is more common than you might expect. “It does happen, and I think a lot of high school students should pursue this more. Don’t be afraid to look for mentors. I think there can be a very valuable resource for your own development and for the development of your project.”

“The first time I worked in the lab it was a project that was my own idea,” says Hyslop. “I was testing out the antibacterial properties of different plant oils. I came to the professor with that and he said I could do it. He basically taught me the procedures and the safety and let me ask questions when needed. It was working with the bacterial strains that he was working with, but it was my own project. Not every science fair project is going to get to the level where you will be doing research in a university, but I think it is an amazing opportunity to get high school students to do something that can really tell them about what they want to do in university.”